The abundant and ceaseless supply of scientific information causes overload. Scientists, no matter how intelligent and hardworking they are, and with the best computers at their disposal, are pushed past the point where they can effectively assess all the available data in a reasonable timescale. Crowdsourcing opens projects to the willing input of many people, some may be specialists in relevant areas and others may be “layman scientists” with skills in other less obviously applicable sectors. And the outcomes are unprecedented.

People are incentivized by various motivations to give their time to apply skills and expertise to mass problem solving. Each individual can be motivated by any combination of entertainment, cash prizes, the perceived chance of a career change or the satisfaction of contributing to a solution to a major issue.

Acknowledged benefits include:

- Innovation and creativity from outside an institutionalized frame of mind

- Building accurate and vast knowledge

- Solving complex multi-layered problems

- Achieving complicated feats within a short span of time

- Removing a cost barrier to market entry by reducing significant internal R&D investment

Whether offering cash prizes or entertainment, crowdsourcing platforms increasingly borrow motivational design features that players are accustomed to in on-screen games. These techniques boost the quantity of input from a higher number of participants, and the quality of input as competitiveness drives individuals to greater effort.

When space exploration was restricted to state monopolies, NASA was the centralized US body receiving all the money, employing all the scientists and running all the missions. Times change. Today there are several private enterprises vying for contracts to put satellites in space or to develop space flight tourism. Cash prizes have provided the motivation for many thousands of people to contribute to decentralized R&D of technology and equipment for space flight.

NASA itself has opened its doors and uses its open innovation NASA Solve program to crowdsource input to a series of challenges, giving people a chance to win cash prizes and the accolade of seeing their name attached to inventions and ideas brought to life.

In the past 12 months NASA has used “citizen scientists” to devise construction technology to create sustainable housing for deep space exploration, study vast numbers of images of planet surfaces, invent multi-functional tools that can be 3D printed in space, and develop software to improve the autonomous capabilities of NASA’s humanoid R5 robot.

Crowdsourcing was also used to develop an alternative to a NASA-backed space flight to return to the Moon. The Google Lunar XPRIZE (GLXP) was a $30m cash prize competition that ran from 2007 through 2018, organized by the X Prize Foundation and sponsored by Google. This was covered in a recent CSW article by Dr Shay Hershkovitz, a leading member of the GLXP team.

Crowdsourcing was also used to develop an alternative to a NASA-backed space flight to return to the Moon. The Google Lunar XPRIZE (GLXP) was a $30m cash prize competition that ran from 2007 through 2018, organized by the X Prize Foundation and sponsored by Google. This was covered in a recent CSW article by Dr Shay Hershkovitz, a leading member of the GLXP team.

Back on planet Earth, Visioneering is XPRIZE’s main channel for designing competitions to solve their shortlist of humanity’s five grandest challenges. The first stage is to crowdsource input on designing the actual competition structures and the prizes to incentivise entries. Providers of the best concepts will then work with XPRIZE to develop robust competitions, and take the stage at their major annual conference. Top of the list of grand challenges is how to provide access to decentralized energy supplies.

Crowdsourcing through on-screen gaming can tackle different issues to cash prize competitions. We humans are very efficient at recognising patterns, still a difficult task for computers and algorithms. Games combine a pleasing interface, a challenging and entertaining problem to solve, and a will to help scientific research. Problems can be broken down into a series of smaller tasks, which when completed by many players can lead to great results.

An iconic example of unprecedented results is the resolution of the crystal structure of the M-PMV (Mason-Pfizer Monkey Virus) retroviral protease, which was very important for developing drugs for AIDS. After more than a 10 year blockage, researchers turned to the online protein-folding game Foldit and its community of gamers solved the protein’s 3D structure inside three weeks.

Games launched on both sides of the Atlantic in 2016 are helping scientists develop treatment for brain diseases that afflict nearly 50 million people, a number expected to almost triple to 130m by 2050. In the US, the Human Computation Institute (HCI) collaborated with Cornell University, University of California-Berkeley, Princeton University, WiredDifferently and SciStarter to develop and launch Stall Catchers, a citizen science game to fight Alzheimer’s disease. By May 2018 there had been over 10,000 players.

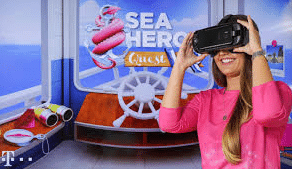

Alzheimer’s Research UK, working with University College London and the University of East Anglia, launched Sea Hero Quest. It is designed for a wider audience than Stall Catchers and in its first year over 3 million players established the first ever benchmark of spatial navigation in humans. Financial backer Deutsche Telekom subsequently funded a VR format to replicate lab-based experiments among broad audiences.

Alzheimer’s Research UK, working with University College London and the University of East Anglia, launched Sea Hero Quest. It is designed for a wider audience than Stall Catchers and in its first year over 3 million players established the first ever benchmark of spatial navigation in humans. Financial backer Deutsche Telekom subsequently funded a VR format to replicate lab-based experiments among broad audiences.

This is but a snapshot of some of the landmark examples of crowdsourcing techniques and the innovation they enable in the fields of medical science and space exploration. What experiences can you contribute, or what trends can you identify to help Crowdsourcing Week’s community understand more about this topic?

Keeping up with new trends and developments in crowdsourcing and the crowd economy overall can be hard work. You’ll find an effective option is to attend our #CSWGlobal18 conference running 24-28 October in Washington, D.C. Thought-leaders and top crowdsourcing practitioners from around the world will take the stage for two days at the iconic Carnegie Institution for Science, followed by an optional two days of expeditions to nearby iconic facilities that have embraced crowdsourcing models.

Confirmed speakers include Amy Kaminski, program executive for prizes and challenges at NASA; Vera Mulyiani, pioneering an urban infrastructure for Mars; Steve Rader, deputy manager of NASA’s Center of Excellence for Collaborative Innovation; Julian Guthrie, journalist and author of How To Make A Spaceship; Elizabeth MacDonald, program scientist at NASA; and Marc Kuchner, a NASA astrophysicist and science communicator. Tickets are available now with some savings that will expire soon. We hope to see you in DC.

Absolutely! Honestly speaking, technologies can help make economies and societies more inclusive and address environmental concerns, but they also pose new challenges. They could disrupt labor markets, exacerbate, or create new inequalities and raise ethical questions.