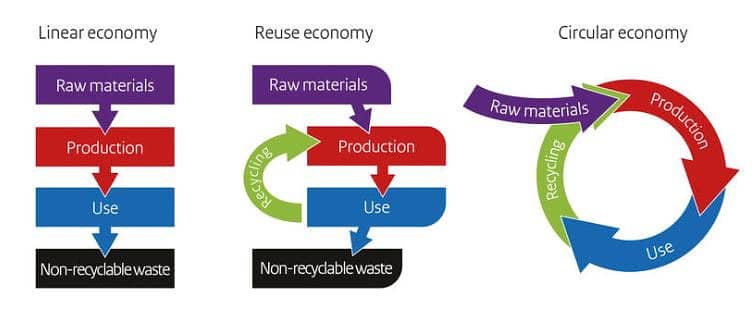

Much of the work and focus in the circular economy is based around disrupting standard linear economy business models of “take-make-waste” to ones where higher proportions of resources can be recycled with minimal disposal. Through using waste as a resource to be recycled rather than disposed of, and by prioritising regenerative resources, we can stretch the lifetime of our planet’s finite resources. Otherwise, in a world where success is largely measured by profits, most company directors are tied to legal requirements to maximise shareholder value. Stock markets reward relentless growth, and everyone chasing growth in a race that will exhaust those finite resources is not sustainable. How hard will it be to make the switch?

Transitioning from a linear to a circular economy

Image source: Netherlands Government

It’s not that circular economy practices are not or cannot be profitable. But where it makes a difference is how ‘value’ is recognised and measured, what it represents to different stakeholders, when it is measured, and how it is distributed. So there is a lot to consider about the extent of the inroads that circular economy techniques and practices can achieve. It’s definitely up against the vested interests of major corporations and their stakeholders to maintain the status quo. 80% of shareholders in the global energy company BP recently voted against adopting tougher measures to tackle climate change.

So far, these words reflect wider sentiment that sets a boundary around the circular economy and restricts it to activities that deplete raw materials to manufacture goods or provide services, whether as an input to products or for energy to fuel the processes. Finding alternatives to slow down the use of resources such as fossil fuels and minerals also has a valuable impact on the climate change crisis, and engages the public at both head and heart touchpoints.

Sharing economy

What can very effectively reduce demand that exhausts finite resources is to share more of what has already been produced, rather than each of us have our own individual items. In terms of material possessions there are sharing economy platforms where we can both lend and borrow a multitude of items. Amsterdam’s Sharing Economy Action Plan features:

- Peerby – an app that connects people who need to borrow or rent an item

- MotoShare – an app that connects motorbike and car owners to those in need of temporary use of one

- LENA – a ‘fashion library’ where customers can rent high quality fashion items on a one-off basis or gain access to the clothing offered via a subscription service

Beyond tangibles

Here at Crowdsourcing Week, our perception of the circular economy extends further to include knowledge. Much of crowdsourcing, and certainly the search for ideas and solutions through open innovation, is based on circular economy practices applied to transferable knowledge and skills. Original thinking within an industry or business sector, with all the work that went into it, should not be left to simply sit where it originated when it could often be applied to other sectors.

Swift and easy collaboration between people from different cultures and mindsets through open innovation programmes can then strengthen and advance that knowledge through previously unimagined connections. This can spark disruptive breakthroughs and innovations, particularly with outsiders’ disregard of, or even unawareness of, established conventions that can constrain the minds of recognised “industry experts.”

Where the circular economy delivers bigger benefits

Given the importance of the circular economy to reducing greenhouse gases it is appropriate to move from looking at it at a personal level to industry sectors. Given their significant contributions to greenhouse gases and climate change, the energy and construction sectors deserve particular attention. The lessons being learned here can apply to many other sectors.

Construction

55% of today’s world population live in cities. By 2050 it will be an estimated 66% of a bigger total population, adding 2.5 billion city dwellers. The rush to build and build means that the second most used liquid in the world after water is concrete, which gives off high levels of carbon emissions as it sets. In 2019 the global construction industry accounted for 38% of the world’s greenhouse gases, according to the United Nations Environment Programme. This covers the material components of the built environment, the energy used to construct buildings and related infrastructure, and the greenhouse gases produced through using the buildings and transport infrastructure to live, work, relax and travel between them.

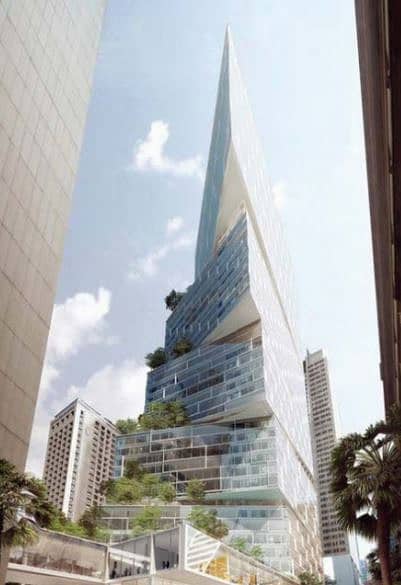

This has given rise to a mantra that “the greenest buildings are ones that already exist.” In Sydney, Australia, new-build sites in the Circular Quay Central Business District ran out long ago, so all construction is on the sites of existing structures. Like most everywhere else, the normal process is demolition and removal to clear a site, then start work on what is usually a taller building. However, developers of the 49-storey Quay Quarter Tower, which will be completed in 2022, kept most of the concrete core of the previous (smaller) building it is replacing. This saved over 7,500 tonnes of CO2, equivalent to the emissions that will be produced in two and a half years of operating the building. Further, the new-build project retained 66% of the previous building’s existing columns, beams and slabs and 95% of its internal walls. In total, the re-use of materials from the existing building delivered a financial saving of an estimated A$130 million.

Bold initiatives like this certainly contribute to Net Zero Carbon targets that many developers, construction companies and property owners are committing to, and aim to achieve through greater use of circular economy techniques. Though assuring the integrity of recycled materials is complicated. Materials used decades earlier may not meet current building regulations or standards. Construction methods were seldomly devised to be reversible and demolition may be the only viable option. Out-of-sight steel inside reinforced concrete, for example, may have corroded or weakened due to other reasons.

Work by a civil engineering firm estimates that 80% of a building’s environmental impact is decided at its early design stages. This is when circular economy measures need to be considered, rather than at the end of a building’s life when the demolition team is being decided. In the meantime, 85% of the buildings that already exist will still be with us in 2050. Initiatives such as “Material Passports” are an attempt to encourage compiling inventories of the materials and products that are in place in a building to identify the extent to which they can be reused in the future.

To boost circular economy practices in the built environment, the UK-based international property company Grosvenor Group is trialling a second-hand market for materials in Central London. It aims to overcome the most cited obstacles to re-using materials that its research uncovered, including factors of uncertain quality and inconsistency of materials, lack of certainty over future availability of materials, and how insurance companies will evaluate risks associated with recycled materials.

As this initiative expands and becomes more widely adopted, they agree blockchain technology has a role to play in providing an immutable central register of what buildings actually consist of, the origin and provenance of those materials, and the stresses they are likely to be subjected to during a building’s lifetime.

In the meantime, for the circular economy model to be more widely adopted, a construction sector expert at the Alliance for Sustainable Building Products said the flagship case studies used within the industry have to move from highly elitist “haute couture catwalk” projects to the less aspirational arena of “shopping mall fast fashion.”

Energy

Greenhouse gases given off by burning fossil fuels are much more evident than those emitted by concrete as it sets. Naturally regenerative and sustainable non-toxic sources include wind, water, tidal, solar and geothermal. Decades of development means energy from regenerative sources the world over is now cheaper as well as cleaner than nuclear.

With a high element of geothermal activity, an equatorial (wet!) climate, and with two mountain chains running almost the full length of the country, Costa Rica has long been a world leader. Since 2014 it has been 95+% reliant on regenerative energy. The misnamed Lake Arenal, close to the volcano of the same name, is Central and South America’s largest man-made reservoir and is used for hydroelectricity.

Pedestrian footfall can now be added to the list of natural power sources. Shoppers, commuters and concert-goers can generate energy by walking on Pavegen’s tech tiles. Slight movement of angled elements of the tiles contribute to the power requirements of the locations that house them. Tiles can be installed in any high footfall location. Pavegen’s largest installation so far is a running track inside a Hong Kong office tower block.

Users of an office block running track in Hong Kong generate power to light it up. Image source: Pavegen

Disposing of or recycling household waste is a major challenge for many countries. What has this to do with energy? Sweden has shown that one person’s rubbish can be someone else’s opportunity. They have developed their household rubbish treatment programmes to such a degree that only 1% of it goes to landfill sites. Since 2017 over half is used for “energy recovery” purposes – they burn it. They burn it in an efficient manner that gives off less greenhouse gases than the methane that would be released to the atmosphere if they buried it in landfill sites. The incineration plants supply heat to a million homes. The process is also an income stream: other countries pay Sweden to take their waste.

Another example of energy benefits from waste, this time agricultural waste, comes from Australia. After early tests, numerous farms will be part of a supply chain for growing food crops, such as maize, barley and wheat. Mass data collection from IoT-linked ground sensors, soil probes, time lapse cameras and drone observations will monitor crop performance both above and below the ground, allowing correct and timely use of organic fertilizer – created from biowaste products. Test results showed improved soil yield, reduced water use, and higher amounts of carbon captured in the soil, all of which protect natural resources and help tackle greenhouse gases. The grains will be sold as food, while the stalks and other crop waste will be converted to renewable fuel pellets.

Crowdfunding supports circular economy initiatives

Crowdsourcing in the circular economy includes generating funding for startup businesses. Traditional lenders have a poor track record of investing in any business sectors where startups are developing ways to disrupt existing marketplaces. Equity crowdfunding provides a route to secure seed stage funding from a number of “armchair investors” who share the aims and values of a business rather than apply the risk assessment analysis of an institutional investor or a VC.

Pavegen’s earliest seed funding was raised through equity crowdfunding, a form of crowdsourcing that raises funding through investors becoming shareholders in private companies. Further institutional backing then came from the Middle East, where there is a need to diversify from a reliance on oil.

Another example is the road building and repair company MacRebur. They replace bitumen in regular road surfacing asphalt with recycled plastic waste. It makes the asphalt cheaper to produce, it has a lower carbon footprint and is more resilient, meaning the surfaces need less frequent maintenance. MacRebur also surfaces airport runways and car parks. In March 2021 the company raised a further £1.2 million to fund plans to open five more manufacturing plants, including locations in the USA and Australia.

Crowdfunding also helped launch Rubies in the Rubble, a high-end food condiments brand made from surplus fruit and vegetables that would otherwise be thrown away. They don’t add refined sugar to their products – they use twice as much fruit as the major brands. And in four years, The Cheeky Panda grew from a reward-based crowdfunding project that targeted £10,000 of orders to an annual turnover of more than £10 million. It makes and sells tissues made from sustainable supplies of bamboo, which has three crops a year and is often just left to rot. Tissues from bamboo are made with a carbon footprint about 65% less than that of tissues made from paper.

B Corps provide longer term circular economy opportunities

Since 2007, an alternative B Corporation structure allows businesses to also incorporate social and environmental impact factors alongside financial returns in their articles of association (articles of incorporation in North America). These articles set out a company’s constitution and the responsibilities of its directors. Under B Corp articles, the purpose of a for-profit company is able to be more than making money for shareholders, and can thus more easily adopt circular economy practices. Nevertheless, they still have to make enough money to remain solvent and accomplish their sustainable and circular social and environmental aims.

Bamboo tissue maker The Cheeky Panda and the open innovation prize challenge platform HeroX are examples of B Corp companies, with formally recorded environmental aims as well as financial ones.

What next for the circular economy?

We’ve shown examples of circular economy practices used around the world. It is a growing trend as it is vital for regenerative and sustainable growth. For it to go beyond individual and piecemeal efforts there are requirements for industry-wide standards, policies and often a regulatory infrastructure. Creation of these sector rules and standards is probably the largest challenge. Which governments or other organizations will and can take on these responsibilities?

Poland, as an example, released its “Roadmap towards the Transition to the Circular Economy” in 2019. Its key aims are to maximise the value of raw materials and resources, and to minimise waste that cannot be re-used or recycled. In particular, Poland has great potential for improvement concerning industrial waste, such as from mining and extraction, industrial processing, and energy production and supply (the primary source of electrical power and heat remains burning coal and lignite).

There are plans for information campaigns to educate the population on the environmental benefits of circular economy principles, and to encourage industry to take appropriate steps. The government will not be shy about legislating if businesses fail to adopt appropriate new business models, with strong cooperation between the ministers responsible for the economy and the environment.

Traditional profit maximisation as a measure of efficient use of resources is no longer going to be the case. Sounds good so far. However, rather significantly, the Polish government’s Roadmap covers its intentions without including a framework for financing its impact on the country’s industries, businesses and citizens.

In an article coming up soon we will tke a look at some of the leading organizations that are lobbying big business and governments to adopt more circular economy principles and behaviours. In the meantime, we welcome any contributions to the debate about crowdsourcing in the circular economy.

0 Comments