Since the 2004 publication of James Surowiecki’s highly influential book, The Wisdom of Crowds, the idea that large groups of people can be smarter than a few individuals, no matter how brilliant, has been gradually gaining prominence in academic circles, business communities, and public opinion.

Crowdsourcing is one of the most popular applications of this idea. Numerous organizations – including corporations, governmental agencies, and nonprofits – have adopted crowdsourcing as an innovation tool to help them address their most pressing business challenges.

However, the practical adoption of crowdsourcing has been far from seamless. Why? Firstly, there is widespread, often completely paralyzing, uncertainty over which business challenges can (or can’t) be solved by crowdsourcing. Secondly, many organizations – especially those new to crowdsourcing – have difficulty “matching” their specific problems to the crowdsourcing platform which is most suitable for solving them.

As a result, crowdsourcing is often used in a suboptimal way, and when the outcome proves disappointing, it is crowdsourcing itself that gets the blame for being ineffective. Periodic calls to “rethink” crowdsourcing regularly appear on the pages of the most respectful business publications.

There is no need to “rethink” crowdsourcing fundamentally. However, there is a need to create a clear understanding of what crowdsourcing is, and how it can be used to create value. Equally important, we need to clarify which crowdsourcing platforms and applications are available in the marketplace and how to apply them to specific crowdsourcing projects.

What Is Crowdsourcing: The Fundamentals

What Is Crowdsourcing: The Fundamentals

Let’s start with defining what crowdsourcing is. This will help us make a clear distinction between crowdsourcing and other knowledge-management tools – such as brainstorming, with which crowdsourcing is regularly confused.

The term “crowdsourcing” was first coined by journalist Jeff Howe in 2006. Howe also provided the original – and, arguably, still the most precise and comprehensive – definition of crowdsourcing, describing it as “the act of taking a job traditionally performed by a designated agent (usually an employee) and outsourcing it to an undefined, generally large group of people in the form of an open call.”

What is very important in this definition is that crowdsourcing is not just about a crowd; first and foremost, it’s about outsourcing a job, a point that is often forgotten in our conversations about crowdsourcing. Simply speaking, crowdsourcing is outsourcing a job to a crowd of external contributors. Or, to rewrite this statement as a simple formula:

Crowdsourcing = a job + a crowd

Crowdsourcing: Two Approaches, Two Objectives

Crowdsourcing: Two Approaches, Two Objectives

Now that we’ve answered the question “what is crowdsourcing”, we now need to address how the methodology can be used to solve business challenges. There are a huge variety of different “jobs” organizations can potentially outsource to a crowd of external contributors. However, it’s possible to reduce all crowdsourcing tasks down to fit within two major approaches: adding capacity and accessing expertise.

Both types have characteristic features and follow their own rules of engagement. Understanding the difference between the two is very important because the lack of such understanding frequently results in the failure of crowdsourcing campaigns. It would, therefore, be useful to discuss these two types of crowdsourcing separately.

Adding the Capacity for Capturing Genius

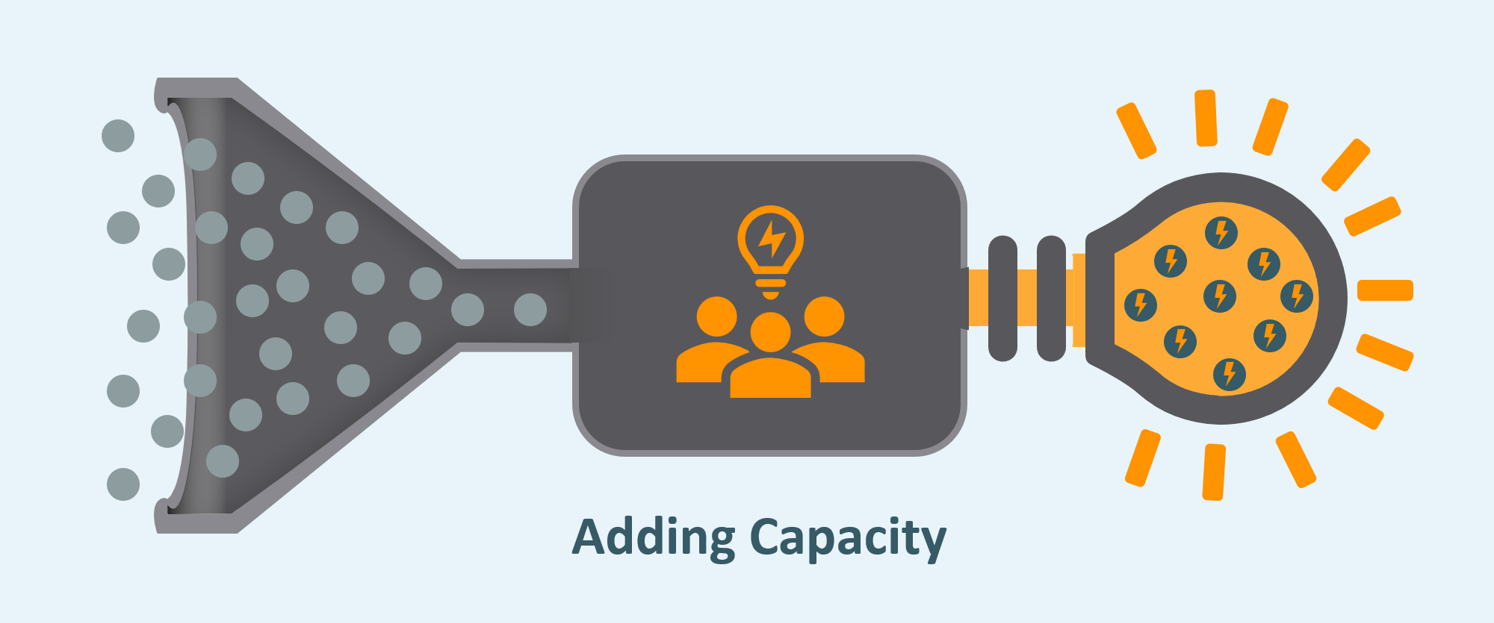

Crowdsourcing by adding capacity is the process of splitting a large job into small, usually identical, parts. A crowd is then assigned to take care of these broken-down tasks, with the whole job being completed quicker as a result.

Another term for “adding capacity” is “microtasking.” Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and ClickWorker represent the most prominent microtasking marketplaces, although certain reservations have been expressed recently about the quality of the Mechanical Turk’s deliverables.

Amazon’s ‘adding capacity’ crowdsourcing initiatives extend far beyond their ‘Mechanical Turk’ system. Recently, Amazon announced plans to create a next-gen Mars rover using crowdsourced insights to inform the design.

The members of the “adding capacity” crowd usually don’t need any special training to perform the job. However, it’s the responsibility of the project sponsor to provide the crowd with clear directions on how each part of the job should be completed. It’s also the sponsor’s responsibility to design a robust protocol for assembling the whole job from its crowdsourced sub-components.

Organizations use the adding capacity crowdsourcing approach when the desired job requires an amount of resources that the organization simply doesn’t have. Take, for example, the Common Voice project by Mozilla. Common Voice is a publicly available database that contains around 1,400 hours of recorded human speech from more than 42,000 contributors in 18 different languages. Obviously, Mozilla couldn’t have created such a database using its 1,200 employees alone.

In most cases, the larger the crowd that is available for adding capacity crowdsourcing, the better. For example, adding extra contributors to the Common Voice project would have allowed Mozilla to expand the database – both in terms of recorded hours of speech and the number of covered languages. In this respect, adding capacity crowdsourcing is clearly different from its accessing expertise counterpart.

A more sophisticated version of adding capacity crowdsourcing, the “flash organization” concept, has been developed to deal with complex, open-ended tasks that can’t be easily broken into smaller identical parts.

Accessing Expertise to Power Innovation

Accessing Expertise to Power Innovation

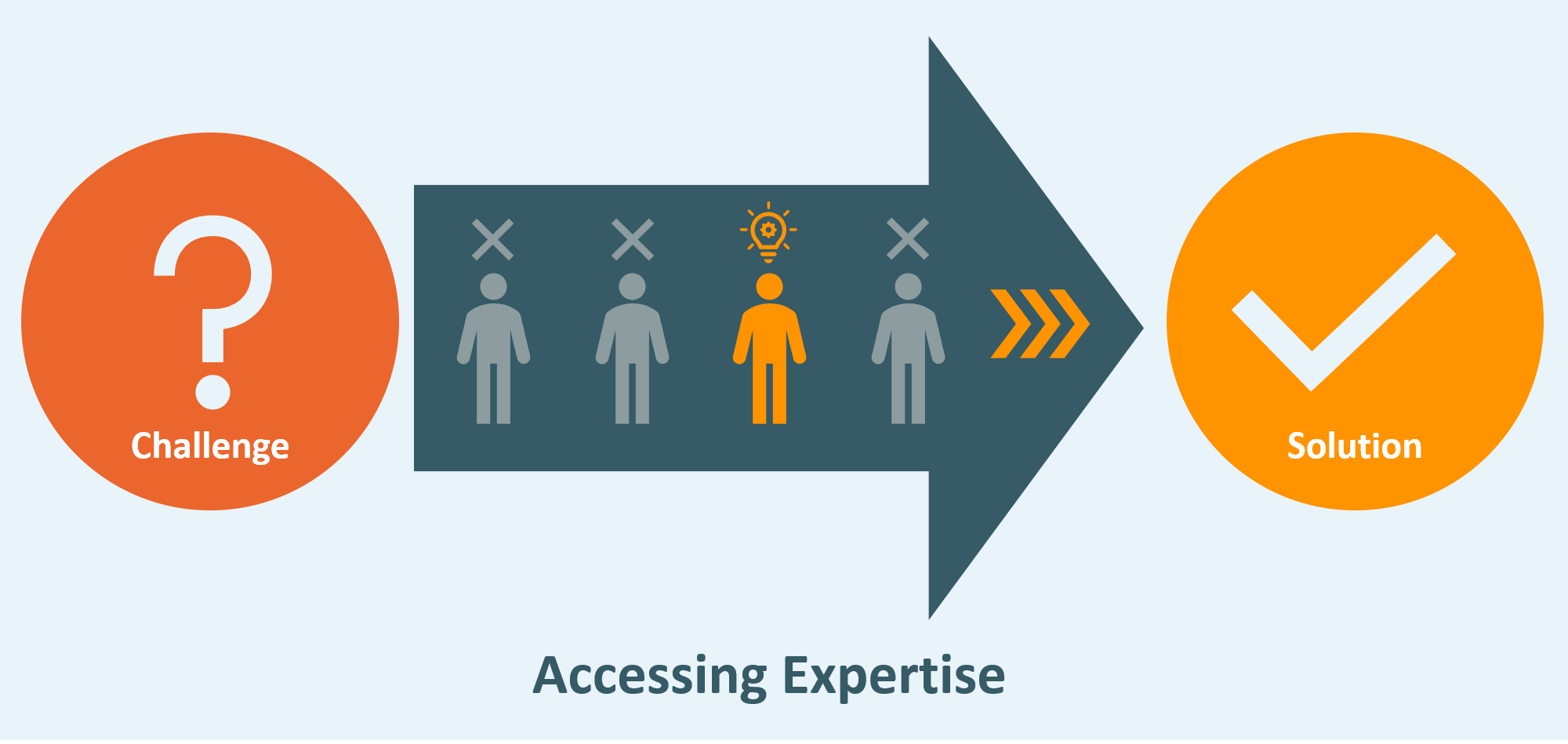

The “accessing expertise” approach to crowdsourcing is essentially the process of exploring the proverbial “wisdom of crowds.” It’s the methodology of collecting expertise, creativity, and skills from anywhere outside the organization. There seems to be no established academic term for “accessing expertise” crowdsourcing, although “crowdsourced innovation” comes very close.

Organizations use “accessing expertise” crowdsourcing not when they need to perform a modular job, but when they want to solve a problem that prevents the organization from achieving an important objective, like designing a new product or optimizing performance.

When launching an “accessing expertise” crowdsourcing campaign, the campaign sponsor must clearly define the problem and explicitly outline the requirements that all successful solutions are expected to meet.

In contrast to “adding capacity”, members of the “accessing expertise” crowd should have the relevant experiences or insights to allow them to solve the problem – and the more sophisticated the problem, the more experienced the members of the crowd are expected to be. Moreover, these days, many complex technical and business problems require completely novel, unexpected, and sometimes unorthodox solutions – meaning that the pool of incoming contributions should include many different ways of solving the problem, out of which only one or a few may turn out to be viable.

The “accessing expertise” crowdsourcing approach works best when it targets crowds that are diverse. This is because the more diverse the crowd, the more varied and creative the insights and ideas gleaned from it. On the other hand, the crowd size by itself is, perhaps, a secondary consideration for “accessing expertise” crowdsourcing. Sure, larger crowds are usually more diverse, but a relatively small yet very diverse crowd can be remarkably successful when tackling the most challenging problems.

“Accessing expertise” crowdsourcing can be further divided into idea generation and problem-solving, which could also be called the “bottom-up” and “top-down” modes of crowdsourcing respectively. Understanding the difference between the two is very important– and this will be addressed in a separate post.

For now, hopefully this post has helped to give you a clearer understanding of crowdsourcing, and how it might be applied to the challenges you’re facing within your respective organizations.

Main image: Rob Curran, Unsplash

0 Comments